“ EVOLUTION OF THE CAMERA VIEWFINDER”

by D. Karl Malkames, ASC

The earliest motion pictures preserved in archives today bear evidence of the ubiquitous static frame within which the action took place with little attempt made to move the camera except when mounted on a moving platform such as a bus, tram or railroad train.

Following is an overview of the role of the camera operator from the very beginning in his control of composition and movement. Unusual skills were required of him as view finders evolved over the years and as cameras became lighter and more mobile.

At the turn of this last century D.W.Griffith’s cameraman, Billy Bitzer, was found cranking out one reel subjects on the fifty pound Mutograph camera which was always tied off in one position. The action being photographed with a 50mm lens was confined to a 28 degree arc of space outlined in many cases by lines drawn on the stage within which the actors performed.

Initially, the usual viewfinder, if any, consisted of a plano concave lens situated near the front side or top of the camera through which the field was observed through a peep hole at the rear. No masks were required as most all early cameras were confined to a 50mm lens.

In 1908 Andre DeBrie introduced his wooden cased ‘Parvo’camera with interchangeable lenses. A viewing tube was provided at the rear to observe an optically erected image as focused on the film at the aperture, existing stock being sufficently translucent. Other contemporary cameras at that time offered this feature although the eyepiece had to be covered to prevent fogging.

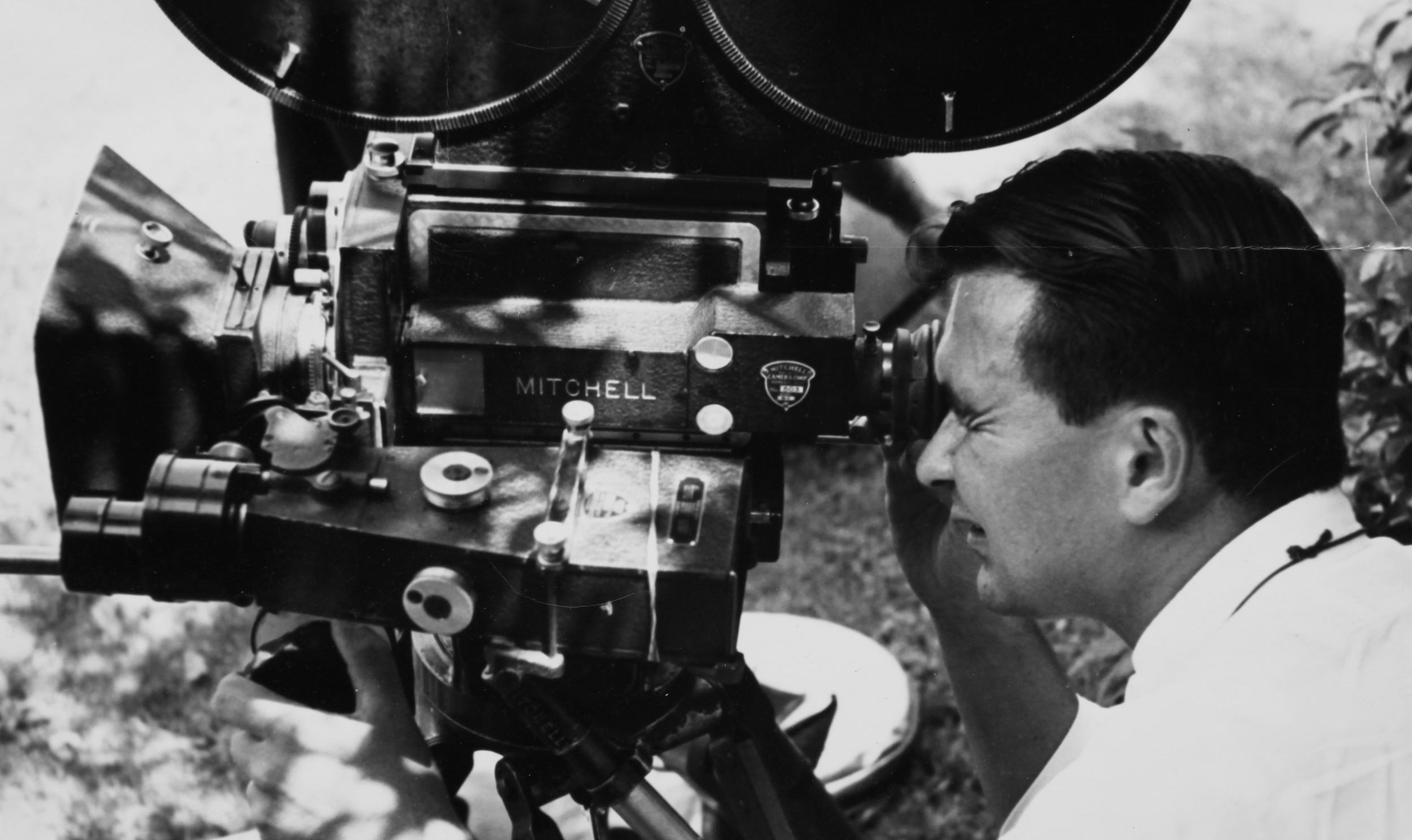

The first gear heads that became available established the directional hand movements for crank turns that would survive to this day. If a cameraman from 1915 were to be transported to any set today on which the latest Moy, Mitchell, Worral or Panavision gearhead is in use he would have no problem adapting his operative skills in panning and tilting. On the other hand he would be most amazed at the luxury of the reflexed viewing that is now taken so for granted.

Before the first World War the so-called ‘Pancake’ Akeley camera presented an unusual number of innovations including an integral gyro controlled pan and tilt mechanism smoothing the movements imparted with a pan handle. Although the original patent specifications indicated a reflex viewfinder system ,the production model offered minimal parallax using matched close coupled finder and objective lenses.

Introduction of the Bell & Howell 2709 studio camera in 1912 provided the precision instrument that became the most common profile seen on American motion picture stages.

Lenses of varying focal lengths were mounted on a turret. The outside view finder provided at that time proffered an inverted image focused with a lens upon a ground glass. This image of course moved in opposing directions relative to pan and tilt requiring an unusual mental adjustment for the operator. In 1920 a compound prism in the viewfinder of the new Mitchell camera finally presented an erect image.

To free the operators hands for the gear head cranks , (unless the camera was motor driven) a flexible shaft at times linked the camera to a separate facility for cranking by an assistant. In the mid 20’s the so-called ‘free head’ controlled with a pan handle came into wider use.

When sound recording invaded the studios in the late 20’s cameras were initially confined to sound proof enclosures that offered no opportunity for movement. The following three decades saw the introduction of custom designed heavy ‘blimps’ or sound deadening housings embracing the camera.

Prior to the debut of the Mitchell BNC, most studios used the Fearless or Raby blimps. They employed a viewfinder linked by cams and cables to geared rings on prime lenses with follow-focus knobs adjusting the finder to the parallax at varying distances.

The parallax involved prior to reflex viewing imposed a complex judgement for the operator. For instance, when dollying into an ‘over-the-shoulder’ shot the final image seen in the viewfinder was far from that being filmed. Only after ‘racking-over’ to view through the taking lens could the composition at the end of the shot be verified.

Another challenge for the operator through the 30’s, 40’s and 50’s was the avoidance of microphone shadows. He worked closely with the mike boom operator during rehearsals to coordinate movements but many a mike or it’s shadow dipped into the scene requiring retakes.

State of the art reflex viewfinders with video taps and remote operation capabilities are luxuries we take for granted today. Only those of us who have experienced this evolution can fully appreciate such progress.